Who are CRNAs?History: Nurse anesthetists have been providing anesthesia care to patients in the United States for more than 150 years. The Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA) credential came into existence in 1956 and, in 1986, CRNAs became the first nursing specialty accorded direct reimbursement rights from Medicare. In 2001, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) changed the federal physician supervision rule for nurse anesthetists to allow state governors to opt out of this facility reimbursement requirement.

Prolific Providers: There are approximately 65,000 practicing CRNAs nationwide. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects CRNA employment will grow significantly faster than average between 2024 and 2034. Rural America: CRNAs represent more than 80% of the anesthesia providers in rural counties. Many rural hospitals are critical access hospitals, which often rely on independently practicing CRNAs for anesthesia care. Half of U.S. rural hospitals use a CRNA-only model for obstetric care, and CRNAs safely deliver pain management care, particularly where there are no physician providers available, saving patients long drives of 75 miles or more. Anesthesia Safety: Numerous peer-reviewed studies have shown that CRNAs are safe, high quality and cost-effective anesthesia professionals who should practice to the full extent of their education and abilities. According to a 2010 study published in the journal Nursing Economic$, CRNAs acting as the sole anesthesia provider are the most cost-effective model for anesthesia delivery, and there is no measurable difference in the quality of care between CRNAs and other anesthesia providers or by anesthesia delivery model. Researchers studying anesthesia safety found no differences in care between nurse anesthetists and physician anesthesiologists based on an exhaustive analysis of research literature published in the United States and around the world, according to a scientific literature review prepared by the Cochrane Collaboration, the internationally recognized authority on evidence-based practice in healthcare. Most recently, a study published in Medical Care (June 2016) found no measurable impact in anesthesia complications from nurse anesthetist scope of practice or practice restrictions.

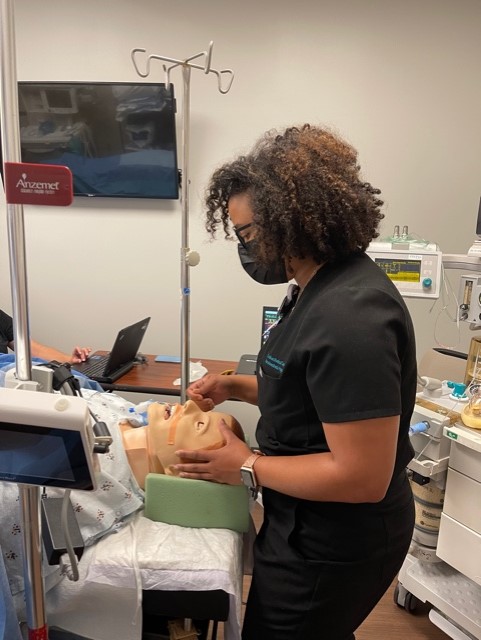

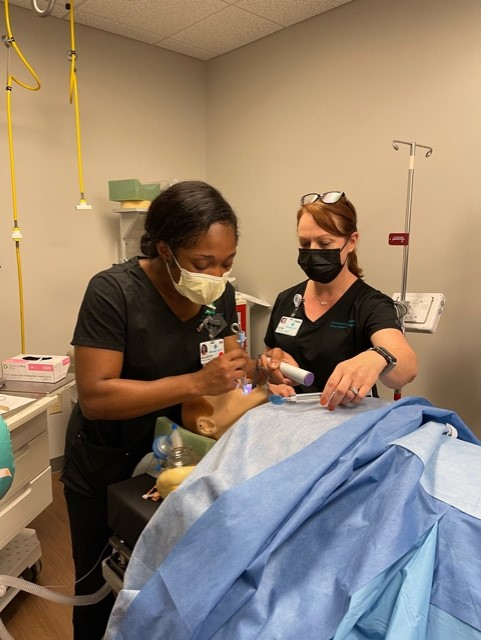

Practice of Nursing: Today, 25 states and territories have opted out of federal supervision requirements, allowing CRNAs to practice autonomously when supported by state law. Autonomy and Responsibility: As advanced practice registered nurses, CRNAs practice with a high degree of autonomy and professional respect. CRNAs are qualified to make independent judgments regarding all aspects of anesthesia care based on their education, licensure, and certification. They are the only anesthesia professionals with critical care experience prior to beginning formal anesthesia education. Practice Settings: CRNAs practice in every setting in which anesthesia is delivered: traditional hospital surgical suites and obstetrical delivery rooms; critical access hospitals; ambulatory surgical centers; ketamine clinics; the offices of dentists, podiatrists, ophthalmologists, plastic surgeons, and pain management specialists; and U.S. military, Public Health Services, and Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare facilities. Military Presence: In 2025, the American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology (AANA) urged the new U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Secretary to grant full practice authority to Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs) within the VA health system to improve veterans’ access to high-quality anesthesia care, citing CRNAs’ extensive training and autonomous practice in other federal systems.

Cost-Efficiency: Based on 2024 salary data, staffing models using CRNAs—either solo or in care teams—demonstrate hundreds of thousands of dollars lower personnel costs than physician-only models. Direct Reimbursement: Legislation passed by Congress in 1986 made nurse anesthetists the first nursing specialty to be accorded direct reimbursement rights under the Medicare program and CRNAs have billed Medicare directly for 100% of the physician fee schedule amount for services. In 2020, U. S. Congress passed legislation that included a nondiscrimination provision to prohibit health plans from discriminating against qualified licensed healthcare professionals, such as CRNAs and other non-physician providers, solely based on their licensure.  Education Requirements: As of 2022 and reinforced now, all new nurse anesthesia students must enroll in doctoral-level programs (DNP or DNAP) for entry into practice. Master’s degrees are no longer accepted for new students. Certification: Before they can become CRNAs, graduates of nurse anesthesia educational programs must pass the National Certification Examination. CPC Program, formerly Recertification: The Continued Professional Certification (CPC) Program, which replaced the former recertification program, focuses on lifelong learning and is based on eight-year periods comprised of two four-year cycles. Each four-year cycle has a set of components that include:

For complete information on all components of the CPC Program, visit NBCRNA/CPC. |